Forces of Nature Click on the thumbnails to explore the trail

Read more about this trail (expand)

“Force”, the invisible agent of nature that provides all living things with motion, was a major obsession for Leonardo - the movement of turbulent water, curling hair and leaves that grow in swirling curves were all manifestations of the same natural force. In order to convey a sense of inherent energy in works of art and engineering, such phenomena must be fully understood

- Enlarge

- Book 1, Fol 6v-7 - Determining the volume of regular and irregular solids c. 1505 © V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum

- Enlarge

- Book 1, Fol 44r - Studies of a pump for perpetual motion © V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum

Codex Forster I, II and III Late 1480s-1494

Since the discovery of the laws of thermodynamics during the mid 19th century, attempts to design perpetual motion machines have been virtually abandoned. But during the Renaissance, the age-old dream of a device capable of operating continuously and supplying useful work without any external source of power was alive and well.

In the belief that spirals and screws might hold a solution, Leonardo applied the principle of the vortex to the problem.

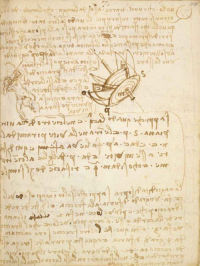

On the right of Codex Forster Fol 44r, Leonardo illustrated one of a number of solutions or “compound screws” involving planar spirals, conical spirals and V-shaped configurations of tubes combined to achieve continuous motion.

The water ascends to the centre of the planar spiral S P and then passes to the pyramidal screw N C running from the point at C to P and acting as an “equidistant lever” to turn the whole apparatus. As the device revolves, further “levers” would come into play.

Despite Leonardo’s seemly precise instructions, the exact configuration or operation is far from clear. After multiple attempts, Leonardo was ultimately forced to concede that the problem was unsolvable.

In Leonardo's words

Oh spectators on perpetual motion, how many vain projects in this search you have created! Go and be the companions of searchers for gold!

The Codex Forster comprises three parchment-bound volumes containing 5 notebooks.

The drawings in these pocket notebooks include studies on mathematics, geometry, weights, and hydraulic machines, carried out at different times between 1490 and 1505.

There is also a well-arranged sequence of theorems dealing with the transformation of geometrical forms such as polygons and polyhedrons of the type Leonardo illustrated for Luca Pacioli’s De Divina Proportione.

- Medium Pen and ink on paper

- Size Ms I 14.5 x 10 cm; Ms II 9.5 x 7 cm; Ms III 9 x 6 cm

- Location Victoria and Albert Museum